My Little Rock Story

Mom graduated from Little Rock High School, a high point in her young life. She was very proud of that accomplishment, considering the challenges of her childhood; one of her dreams was that I, her son, would also graduate from that venerable, and widely-known, institution. Our house was only seven city blocks from the school and, throughout childhood, I would see ”big kids” walking to and from the school. On weekends, as a child, I recall sneaking off with my older brother to smoke cigarettes on the school grounds because we could hide in the bushes. And we would climb up the fire escape slide, so we could then slide back down. Yes, in time, I would walk those halls of learning and follow Mom’s path to graduation, but I treasure those early childhood memories.

Mom graduated from Little Rock High School, a high point in her young life. She was very proud of that accomplishment, considering the challenges of her childhood; one of her dreams was that I, her son, would also graduate from that venerable, and widely-known, institution. Our house was only seven city blocks from the school and, throughout childhood, I would see ”big kids” walking to and from the school. On weekends, as a child, I recall sneaking off with my older brother to smoke cigarettes on the school grounds because we could hide in the bushes. And we would climb up the fire escape slide, so we could then slide back down. Yes, in time, I would walk those halls of learning and follow Mom’s path to graduation, but I treasure those early childhood memories.

But graduating there was not to be. My sophomore year was spent there, and I recall becoming lost more than once in attempting to find my next class: the building was huge to my young mind. My life changed, though, at the beginning of my junior year, 1957. This was the year that the school became integrated, with much national publicity on the story of nine brave (VERY brave) young African-Americans who enrolled in the school. I recall seeing large crowds of white men, standing across from the school and yelling insults to them, and I also recall seeing the famed 101st Airborne Division standing guard with fixed bayonets. This was not a sight one wanted to see at a public high school. Overall, this was a significant event, one that needed to happen to finally end the Jim Crow separation of students with that artificial ‘separate but equal’ framework for educating children. I feel honored to have had a small part in that. To see it happening, to hear it, to know it was within sight of my parent’s home, left a permanent scar.

But graduating there was not to be. My sophomore year was spent there, and I recall becoming lost more than once in attempting to find my next class: the building was huge to my young mind. My life changed, though, at the beginning of my junior year, 1957. This was the year that the school became integrated, with much national publicity on the story of nine brave (VERY brave) young African-Americans who enrolled in the school. I recall seeing large crowds of white men, standing across from the school and yelling insults to them, and I also recall seeing the famed 101st Airborne Division standing guard with fixed bayonets. This was not a sight one wanted to see at a public high school. Overall, this was a significant event, one that needed to happen to finally end the Jim Crow separation of students with that artificial ‘separate but equal’ framework for educating children. I feel honored to have had a small part in that. To see it happening, to hear it, to know it was within sight of my parent’s home, left a permanent scar.

But that is not my story. That particular story has been told many times, and I cannot improve upon it. This is my story, about what came later: the lost year for Little Rock students of high school age.

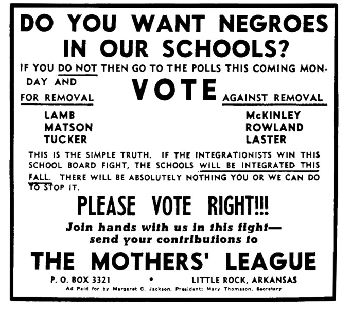

That first year ended peacefully, and my expectation was that school would resume normally in 1958. The soldiers had gone home, and life seemed more stable—but that was not to be. For the 1958-59 school year, the powers that be, emboldened by white parents, decided that having NO school was better than having a school where we delicate, fragile, white kids would be required to associate with children of another color. No school at all. None. Yes, that was their decision. No school. This decision was insane, but that was what we faced. Although the prior year would go down in history for its story of integrating southern schools, the school year of 1958-59 would be known as the ‘lost year.’ My story speaks to a safety net cast for white kids, yet there was none for students of color. The damage to so many lives has never been contemplated or accepted.

That well-intended, but poorly-reasoned, decision pushed hundreds of students over an academic cliff. Many stayed home that year, some had out-of-city relatives to live with, some scrambled to find openings in nearby school districts, but that still left many with no options. That group included me. Fortunately, a group of citizens hurriedly formed a ‘school’ that allowed white students. Not accredited at the start, occupying an old two-story, building, staffed by whatever teachers could be recruited to teach, enrollment began immediately. That was to be my glorious senior year. Temporary buildings were constructed on the lawn to handle all three grades (10 through 12), but this was never considered by students to be a real school. The name: Thomas J. Raney High School. No guidance counselors, no sports (other than a basketball team we cobbled together, and a small track team). This school was eventually accredited, but was it for academic performance, or a political necessity? I shall never know, but I have my opinion on that. Did my education continue? Yes, it did. Were my teachers qualified. Yes, I respected all of them. Was this school necessary? No, this lost year put a black mark on Arkansas and on the people who decided to close public schools.

That well-intended, but poorly-reasoned, decision pushed hundreds of students over an academic cliff. Many stayed home that year, some had out-of-city relatives to live with, some scrambled to find openings in nearby school districts, but that still left many with no options. That group included me. Fortunately, a group of citizens hurriedly formed a ‘school’ that allowed white students. Not accredited at the start, occupying an old two-story, building, staffed by whatever teachers could be recruited to teach, enrollment began immediately. That was to be my glorious senior year. Temporary buildings were constructed on the lawn to handle all three grades (10 through 12), but this was never considered by students to be a real school. The name: Thomas J. Raney High School. No guidance counselors, no sports (other than a basketball team we cobbled together, and a small track team). This school was eventually accredited, but was it for academic performance, or a political necessity? I shall never know, but I have my opinion on that. Did my education continue? Yes, it did. Were my teachers qualified. Yes, I respected all of them. Was this school necessary? No, this lost year put a black mark on Arkansas and on the people who decided to close public schools.

Or did it? The Gallup Poll in 1958 listed the then governor at the heart of the segregation crisis, Orval Faubus, as one of the “Ten Men in the World Most Admired by Americans.” People may look back on the travesty of the Little Rock integration crisis with shame, but that Gallup Poll tells us a different message, a message we find repugnant today. Despite the passage of years, I still have trouble accepting that adults of the time found it morally justified to stop the education of their youth. This was all so wrong and so unnecessary. My life moved on; I treasure my memories, but I had wished for better. Over sixty years have passed since then. And we still have a way to go. We share this world. We face many challenges in society, and skin color is not one of them.

Those other students who attended Thomas J. Raney High continued to gather periodically in later years to reminisce on the blow dealt them by the voters who closed their school. Although I never attended those reunions, I did maintain a reunion website for them at https://tjraneyhs.davidkirk.org/. By joint agreement, the site was closed to future updates on June 22, 2022.

Today, memories (or even knowledge) of that lost year are fading. The ill-thought decision of a few racists damaged the initial foray into adulthood of hundreds, maybe thousands, of young people: the students at Raney High, the students who left families to live with relatives during the year, the non-white students and white students who also sat out that year for lack of options, or who joined the military to pursue a GED education alternative. So much damage to so many, caused by so few. When will racism finally die?