My Cars and I

Cars always were important to me, going back to Dad’s 1939 Nash with the floor shift and weirdly-shaped headlights. That car saw its final days when it broke down when the family was 50 miles into a trip to see relatives. As a child, even that was exciting, as I had never been in an auto repair shop, and we were there all day. The mechanics even let me play with the sliding roller that let them slide under cars. Trips were important back then; I recall Mom was all gussied up in her Sunday best, as was Dad. That day was the only one of my childhood where cars failed me.

That’s because Dad bought a new 1950 Ford when we returned home. Being frugal, the car had no options, such as a radio. Fortunately, the heater was standard equipment — but that was it. This was my first education on the importance of factoring in a device’s complexity and possibility of failure when buying anything. Clocks might break, so there was no clock. Automatic transmissions were complicated, so ours had a manual shift. Air conditioning? I knew better than to ask. Seven years later, I would learn to drive the car, stumbling through the gears until, after 15-20 minutes of practicing in a parking lot, Dad directed me to the road to drive home. Yes, I still have visions of the seemingly infinite cars on the road and my fear of smashing into all of them. Dad didn’t realize it, but he gave me a permanent memory of that experience with him. Treasured.

But this post is about MY cars, my experiences, not Dad’s — but that look back was vital to refresh the memories. My first car was a honeymoon; I respected it, and our relationship was sweet. It was a 1949 Hudson coupe, letting me fantasize about the Hudsons that were cleaning up on the stock car racing circuit. But that was my first car, and that happy emotion of having a car to love and cherish would not be my future. Instead, my life with cars was to be doomed to failure, forever failing to achieve the joy of which I dreamed. Oh, there would be other cars in my life, cars that were reliable, safe, and pleasant to drive, but ALL of them were selected by my dear wife; it was the cars I picked that always went south.

So, on that ‘49 Hudson, I mentioned: It was HUGE, at least to me. A two-door coupe, with overdrive. So excited was I that I would daily offer to drive other students home, students I didn’t even know. I was in 10th grade, the spring of 1957, and feeling full of myself. Unfortunately, the car barely lasted a month before the front end developed problems, a curse that would follow me throughout my life. Cars I buy just never work.

A ‘51 Ford coupe came next: sleek, black, and sexy. V-8, stick-shift, I was in love. But, I didn’t know much about maintenance and, after a few months, on a cold morning, the engine block developed a crack because I hadn’t installed any antifreeze. This was a sad parting, as my girlfriend also liked the car. It was with this delightful car that I experienced my first ticket: unsafe driving. (Well, that was the officer’s opinion. To me, it was late at night, there were no cars on the road except mine, so I was happily weaving from one side of the road to the other. Harmless, right?)

A ‘51 Chevrolet coupe was my next love, with a light green color and a radio. Dad located this buy for me, and it was in pristine condition, a condition that would not last under my desire to use the car for personal expression. From reading many car magazines, I was convinced that this Chevy was ripe for my customizing talents. First, I ripped the holding strip from the center of the hood, replacing it with chrome that almost fit. The chrome on the trunk lid was removed so I could fill the remaining holes with Bondo, sand, and apply a shade of Green that didn’t match. Next, I bought a used set of dual exhausts to give the car a sporty sound. Purchasing them required that I remove them from the other person’s car and replace them with exhaust from my car, a task that took many hours on a Sunday afternoon. Eliminating the continuous rattle was never a success, but the exhaust noise sounded great (to me).

With these successes, I decided to make the engine sound powerful (since I didn’t have the $$$ to achieve that goal) by disconnecting the vacuum connection. Later, I learned that doing such would burn the valves, but I did achieve the rough idle that indicated power. To display my new “hot rod” to a friend, I pressed the gas pedal to the floor. The car leaped forward a foot or two and stopped; my exuberant rush had broken the drive shaft. To my embarrassment, the car had to be towed away to be repaired.

Now repentant of my misuse of the Chevy, I committed to focus on good maintenance, with my first new task being to change the oil in the engine. That went well until I later discovered I had accidentally left an oil leak. Sadly, by the time I was fully aware, the engine needed rebuilding. At this time, Dad stepped in, paid a body shop to fix the damage created by his “artistic” son, and sold the car. My lesson was learned, or so we thought.

By now, summer had come. A 1950 Chevy convertible, in somewhat sad condition, was my newest chariot. Dad helped me pick it out, and I think he liked this one because it looked on its last legs and would be a car I would hesitate to change. He was right. Just keeping it running was all I could do. The gas tank itself leaked, and I bought some “magic” goop to apply to stop the leak (like, yeah, that would work only to a teenager’s hopes). Other than continually watching for gas leaks, that car gave me some smiles, but its life with me was only that summer.

By now, I was a senior in high school, mature and beyond the stupid mistakes of my past. Yessiree, I now was driving a staid, ‘54 Chevy coupe, two-tone, really an attractive car for the time. My watchword was “leave it alone.” That strategy worked well, letting our relationship survive most of that senior year — but the full truth showed my maturity was still lacking. Winter came, and Dad offered to have chains put on the tires to ensure I didn’t have an accident on the many icy roads.

That worked well, as I was able to safely negotiate the harsh winter days. But eventually, warmer weather came — and the chains remained. My thoughts were that cold weather might return, so leave the chains on. Plus, taking them off would be a chore. So, I just kept driving, ignoring the ongoing rattle of chains on asphalt. Well, I kept driving that way until I noticed the chains had seriously damaged all four tires, having cut dangerously into the sidewalls. My dear parents, I’m sure, were glad to see this car sold. My curse was ongoing; selling the car only postponed my future failures.

Time passed. As a young adult, I married the girl of my dreams, happily still suffering with me. Being on our own, without a penny in the bank, I found a well-worn 1950 Chevy coupe, 95,000 beat-up miles, sloppily hand-painted, but I was sure it would last at least a year, a belief that would soon prove to have been overly optimistic.

In six months, the car went through seven fan belts, four flat tires (two within 10 minutes of each other), a broken timing gear that required a major overhaul (done at night, lying under the car), and a holed piston that required ANOTHER major overhaul, plus a need to do a valve overhaul by removing parts of the engine and grinding valves in our small living room. On the way to visit my wife’s parents, the transmission refused to enter third gear, so we did the last hundred miles in second gear, with the car heaving its’ last gasp in their driveway.

Never again would I buy a car in such poor condition. Reliability was the priority for us. So, the next day, we visited a local car lot where I discovered a beautiful 1958 Edsel, only a few years old, and it looked like new. Wow! On the first day, we took a highway trip of several hours, just enjoying the fabulous car and enjoying its many amenities. This was the beauty that would provide luxury and reliability for years and years. I was to spend many months away from my wife with the military and was confident this car would provide her with the safety and reliability that she deserved. How could I be so wrong?

That’s right. Within three months, just THREE months, my wife wrote to me, explaining the serious problem that had been found in the drivetrain and the expense of fixing it, plus sharing a photo of the rust that was rapidly eating that lovely car. She also sent a photo of the 1963 Valiant she had purchased to replace the Edsel. This was her FIRST car purchase, and that car was a jewel. Yes, it wasn’t fancy, with no big engine, and no fancy paint, but it remained with us for many good years. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I would never again be the one to decide the car for our family transportation; my wife would be the one from here on.

Yes, from that ‘63 Valiant until today, we have had reliable, safe, cars for our transportation. But I still had this need for occasionally picking my car for driving to work while she kept the family car. Was I now ready to do this on my own? It was not to be. Having secured a good job with a strong future, I decided a sports car should be my daily transportation, and a red, 1959 MG-A was my next purchase. Ill-advised by my dear wife, but I was in love with the car, and she realized that I would need to learn again about cars.

The MG-A gave me many smiles, as I almost weekly enjoyed adjusting the valves and looking at the engine, and taking short drives in the neighborhood. What I had overlooked was that the frame was rusted and, when opening the battery compartment, I noticed the battery was clinging precariously to the rotting frame. Buying the car had its financial price as well: my wife had reminded me before buying it that our budget couldn’t afford the insurance or periodic maintenance that would be required. Sadly, the car left our life.

Realizing a tight budget, I vowed to be more careful, buying a cheap (VERY cheap) 1962 Buick Electra for my commute to my job. The headlights were puttied in place, and one side of the car was heavily rusted, but it worked. The sheriff stopped me once because the headlights weren’t working, and the electric windows worked only occasionally. I eventually sold the car with a newspaper ad, and the car broke down on the way to the new owner’s house. One more failure.

Transportation to work I still needed, and a sweet 1960 Sunbeam Alpine roadster was available. Hey, it looked similar to the MG-A, and didn’t have rust and mileage was low. What’s not to like? In love again was I. The first thing I did after buying it was to park it in our garage to examine the engine in detail. I noticed the fuel line was loose and contemplated taking it to a local auto repair shop, but decided the item was an easy fix, so I would do it myself. Fixing it would take just a few minutes, so I proceeded to undo the line to re-tighten it.

Well, at this point, physics came into play. See, our water heater (gas-powered) was also in the garage, and the fumes from the open fuel line reached the pilot light on the water heater. Yes, the car burst into flames in the garage. Hurriedly, I pulled the car from the garage, while the local fire department came and dowsed the fire. The damage was only smoke, nothing serious, but the car was totaled, and we needed to repaint much of the house to remove the smoke damage. It was my moment of fame; the fire and car were on the 6 o’clock TV news that night. Looking back, I should have taken the car to the repair shop. But the work seemed so small. It wasn’t my fault; it was the fault of the water heater.

Life went on. A new job, a big promotion, and a 1958 Corvette convertible became my joy. A Corvette. Wow! Beyond my dreams, of owning my own Corvette. Was I happy? Does a cow moo? I was delirious. Okay, I admit that the car had not enjoyed a happy life before being mine. Many miles and little maintenance, yet I remained confident. There were many happy miles… until the day the engine wouldn’t start. What began as a daily call to the local gas station for a truck to come give the car a push start. Every day. Again, I had purchased a car that needed serious work. Later, I was to learn that the timing chain had slipped and a major overhaul was needed. Reliability reached such a low that I needed to leave the engine running when browsing car lots for a replacement. The bloom was off this rose.

Years would pass. Thankfully, with my dear wife’s help, we acquired two new cars a few years apart, so I had a reliable car for a few years, a sweet 1968 Renault R10, mechanically far advanced over other cars of the time. But I would eventually want a bigger car.

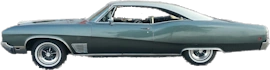

And so, I found a 1968 Buick Wildcat hardtop. Beautiful, sexy, and BIG. My rationalization was that, due to its immense size, I would be safer on the interstate. Fuel economy was not a concern at the time. Confidently easing onto the interstate to drive to work that first day, I mashed the throttle to enter the traffic lane, only to notice a nasty sound emanating from under the hood. What could it be? On returning home that night, I raised the hood and manually moved the accelerator rod on the carburetor to see what happened when the engine’s rpm increased. What I discovered was that an engine mount was broken, allowing the engine to lift from the frame during acceleration. What was I to do? Such an expensive repair was beyond my budget, and I had owned the car for JUST ONE DAY.

My solution was simple: accelerate more slowly. That worked but left me forever knowing the weakness hiding under the hood. my solution worked well, letting me drive the car for several months with no problems. To add to its reliability, I decided to give the engine a tune-up by installing new points, a new condenser, and new spark plugs. Doing that gave me a sense of involvement, and the engine sounded strong after my work.

Unfortunately, while driving to work on the interstate the next day, the engine quit. It just died. It died right at an interconnection of TWO interstates, right at my exit. I walked off the interstate to my office, called a tow truck, and waited to hear of the repair. The problem? Remember those new points I installed? They had broken. I had purchased an off-brand to save a dollar or two instead of buying the name-brand product. I wasn’t learning, was I? My doom with cars would never die. Shortly thereafter, the starter broke. Another tow truck. Over a few months, this repeated three times until I finally realized that something was causing every starter to break. A stranger bought the Buick from me, even though I explained the problems. He was as doomed to buying bad cars as I was.

Today, I am comfortable with our car. My dear wife picked it out with me and gave her approval. We have had the car now for six years without the slightest hiccup. Strong, safe, reliable, always starts, easy to drive, quiet, somewhat boring, and I leave it alone. Whenever it needs attention, which is only for annual checkups, it goes to the dealer. Life is good.

So, what did all of this teach me? It taught me that the old saw “If at first you don’t succeed, try try again.” is wrong, completely wrong, horribly wrong advice to give to anyone. There are issues in life where we desire to excel, but do not have the skill, attitude, intelligence, talent, or commitment to succeed. The phrase would serve us better as “If at first you don’t succeed, try once more and then move on.” And that is where I stand today. I had fantasized that I was a typical backyard auto mechanic and managed to continue that belief through my attraction to many cars. My time would have been better spent by just enjoying my cars and leaving it to others to keep them running. That attitude applies to our best time management; we do not need to master all of our interests. Instead, we need to focus on our strengths, not continue to attempt to repair our shortcomings. (This post could apply equally to my disastrous attempt to learn to sing, but that’s another sad story.)